[For articles on the “Sabbath of Va-Ishlach" in Hebrew, click here]

Updated on December 8, 2022Rabbi Dr. Yossi Feintuch was born in Afula and holds a Ph.D. in American history from Emory University in Atlanta. He taught American history at Ben-Gurion University.

Author of the book US Policy on Jerusalem.

He is the rabbi of Congregation Shalom Bayit in Bend, Oregon.

* * *

Tucked away at the end of our weekly portion Va-Ishlach is a boring long list of Esau’s bloodline; it is uninspiring and ostensibly irrelevant to the Torah. And yet, almost without noticing it we read there about one Timna, apparently -- so the Rabbis tell us -- from a royal household. Timna was a concubine to Elifaz, Esau’s son. And she bore him a son who was named Amalek.

Still, what is so important in reading out publicly at the synagogue the chronicle of Esau’s family tree in-as-much- as we read out the Sh’ma, the Ten Commandments or about the Exodus – why is this stuff given an equal time? Might it be because of a hidden message, a story behind a story that awaits us there to discover and wise us up?

The Talmud comes to our help by telling us that Timna, who was impressed with the Children of Jacob’s good ways and noticed their worthy ethics, sought to convert and become a Hebrew. Inexplicably, she was rejected by Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Still determined to be a part of the Hebrews she was willing to turn even to a fringe of that Hebrew nation, the House of Esau, and become a concubine there, rather than luxuriate as a royalty elsewhere. Elifaz, Isaac’s grandson, spent much time with him and mirrored his finest values. But Amalek, Timna and Elifaz's son, will be a continuous source of distressful trouble to the Hebrews, through the nation that he would birth, because they rejected his mother from becoming one of them. Indeed, right after the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt, Amalek was the first nation to attack the Hebrews from the rear, where the weaker Israelites straggled. And it continued to harass and battle the Jews even through Haman, one of its descendants, who plotted to undo the Jews of Persia.

Had Timna been accepted by either patriarch one may assume that Amalek would not have been born, or would have no grounds to be Israel’s foremost hater. It is rather disconcerting that even Abraham, who together with Sara brought many others to join the Hebrew nation -- ''and the souls that they had gotten in Haran'' (Genesis 12:5) -- said ‘’no’’ to Timna; history would have been totally different had he said ‘’yes’’.

Needless to say, this Talmudic musing is not factual but it seeks to teach us pertinent stuff. Indeed, it could very well be that Timna’s son, Amalek, was a great and loving dude, but for the Rabbis of yore Amalek was Haman with whose nation God has an enduring war. This spirit of Amalek sprang from the fertile ground -- as the Rabbis teach -- even from Amalek's grandfather, Esau. Rabbinically-speaking Esau is Israel’s foremost foe (including being a progenitor of Rome and other evil arch-enemies). Indeed, it must have been Esau who prejudiced Amalek, his grandson, against the Hebrews.

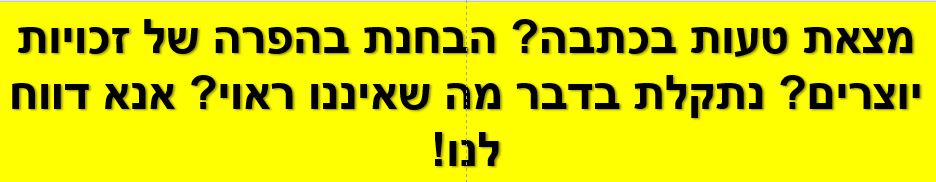

[Picture: This spirit of Amalek sprang from the fertile ground -- as the Rabbis teach -- even from Amalek's grandfather, Esau... Bible paintings / Remembrance of the Amalek War / Painting: Ahuva Klein (c)]

This despite the fact that the Torah depicts Esau as a committed and dedicated son to his parents, Rebecca and Isaac. Esau was always ready to fulfill his father and mother’s wishes, including a marriage within the clan. And then on the basis of hearsay that Rebecca was willing to accept from anonymous hirelings who had reported to her that they overheard Esau saying in his heart that his wish was to kill Jacob, though not being ready yet to do so, Jacob was sent off for his safety. And it is Esau who stayed home to continue and honour his parents, while Jacob did not send them even once ''New Year cards'' from Haran, where he would stay for some two decades. And Rebecca, who sent him off away from Esau’s presumed menace for no solid or verified reason to justify it, would never see Jacob again.

All in all, it is Esau who concedes the land of Canaan to eventually become the land of Israel, so that Jacob’s clan would be the only Hebrew entity claiming it as its home. Herein Esau evinces his magnitude as he understands that Jacob desired to have this land that will be named after his divinely-acquired name – Yisrael – by far stronger than his own wish for Canaan to be named the Land of Esau… Hence, he emigrated with all that he had to Seir. Rather than hate him – as the Rabbis tell us -- Esau loved Jacob with causeless or purposeless love, or ‘Ahavat hinam -- and he desired nothing from Jacob’s appeasing and kowtowing lavish gifts, saying to him: “I have enough of my own, my brother’’.

Now, there is nothing in the Torah to even allude to one Timna seeking thrice to enter the Hebrew nation by marrying into the Hebrew ranks only to be rebuffed. But when you explain that she only ended up in the Esau clan by default, and when you depict Esau as Israel’s arch-nemesis it would become clear why Amalek, Timna’s son and Esau’s grandson, would become this nation’s boogeyman. The fault, then, was in the Jewish conversion protocol, not that it had existed in the days of the patriarchs. Rather than bring the genuinely interested folks into the ranks in a simple and fast procedure, it pushed them away. When the Rabbis lament that neither Abraham, nor Isaac, or Jacob was willing to accept her – presumably being too stringent and picky in their demands -- they see how Timna was pushed into Esau’s camp, and why her son Amalek would be so hostile to the Hebrews throughout the generations. And it could have been avoided.

[Picture: Rather than hate him – as the Rabbis tell us -- Esau loved Jacob with causeless or purposeless love, or ‘Ahavat hinam -- and he desired nothing from Jacob’s appeasing and kowtowing lavish gifts, saying to him: “I have enough of my own, my brother’’. Public domain]

And this makes perfect sense when we observe in the same Torah portion what happened to the men of Shechem who genuinely and earnestly sought to convert into the Jacob/Israel clan. Indeed, they submitted to the ritual of circumcision -- a veritable surgical procedure for adults -- only to be massacred through nefarious guile, for Shimon and Levi did not trust the sincerity of those wanting to convert.

[Picture: the massacre of the people of Nablus. The image is in the public domain]

The wanton massacre in Shechem betrays a disposition of genetic purity, harboured by Shimon and Levi, that could not accept a conversion for the purpose of marriage, even when the woman herself is a Hebrew, like Dinah, Leah and Jacob’s daughter.

In vetoing so atrociously the effective conversion of the Shechemite males, Shimon and Levi ‘’stirred up trouble’’ for Jacob, making him ‘’stink among the land’s inhabitants’’ (Genesis 34:30). Jacob would subsequently decree for them a future dispersal among the eventual tribes that his other sons would grow into with no independent existence (49:6). ‘’Imagine a Torah that, instead of telling about battles and the eventual conquest of the local inhabitants by the Israelites, told us about how the Israelites and the Hivites made peace and lived side by side as neighbors, with most of the locals joining Abraham’s religion as converts. It could have been a lasting, spiritual coup–one that could have served as a model for succeeding generations including our own’’ (Naomi Graetz in The Missed Opportunity for Intermarriage and Conversion in the Story of Dinah).

In rejecting Timna from marrying a Hebrew, the patriarchs created an everlasting enemy for their descendants – Amalek. But in connecting the dots on the eminent 2nd Century Rabbi Akiva the Rabbis called effectively for a correction in the stiff conversion protocol of their days projected on the Hebrew patriarchs' ''nay'' to Timna. Thus, Rabbi Akiva's parents must have been of an Amalek descent before they converted, but presumably hid that fact, or even better were never asked about it. Their conversion would facilitate for their son, Akivah, a place in B’nei Brak, where Akiva would learn Torah, even as a descendant of Haman, thus pointing out that even ex-Amalekites were able to convert and attend a major Torah learning center.

![[Picture: Had Timna been accepted by either patriarch one may assume that Amalek would not have been born, or would have no grounds to be Israel’s foremost hater... freebibleimages]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/מלחמות-עמלק.jpg)

![[Picture: This spirit of Amalek sprang from the fertile ground -- as the Rabbis teach -- even from Amalek's grandfather, Esau... Bible paintings / Remembrance of the Amalek War / Painting: Ahuva Klein (c)]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/אהובה-קליין-עמלק.jpg)

![[Picture: Rather than hate him – as the Rabbis tell us -- Esau loved Jacob with causeless or purposeless love, or ‘Ahavat hinam -- and he desired nothing from Jacob’s appeasing and kowtowing lavish gifts, saying to him: “I have enough of my own, my brother’’. Public domain]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/מפגש-יעקב-ועשיו-אייץ.jpg)

![[In the photo: the massacre of the people of Nablus. The image is in the public domain]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/הנקמה-באנשי-שכם-197x300.jpg)