[For articles on the “Sabbath of TRUMA" in Hebrew, click here]

Updated on February 21, 2023Rabbi Dr. Yossi Feintuch was born in Afula and holds a Ph.D. in American history from Emory University in Atlanta. He taught American history at Ben-Gurion University.

Author of the book US Policy on Jerusalem.

He is the rabbi of Congregation Shalom Bayit in Bend, Oregon.

* * *

When the drought was alarming the community requested their Rabbi to hold an assembly in the outdoors and beseech Heaven for rain to save their seedlings from withering in the ground. The vigil was huge as it was truly a case of to be or not be. When the Rabbi would not start the prayers a long time after the fixed hour for the communal petition, someone cried out: ''Rabbi, what's holding you off? Start the prayer already''. And the Rabbi retorted: ''None of you has brought either an umbrella or a raincoat with you. You do not really believe in the power of prayer which you had asked for. You do not walk your talk, and Heaven would not listen to us, we whose words of mouth do not reflect our inner beliefs. Believe in the power of prayer and soon you will see results. Now, let's pray, even as Rabbi Akiva did at such a dire hour: Avinu Malkenu..."

Lack of sincerity is a serious flaw which the Rabbi in this fictional tale had bespoken of. The prophets decried and fulminated against hypocrisy that was exhibited in the way that Amos put it: ''Remove from before Me the multitude of your songs, and the music of your lutes I will not hear'' until you act justly and righteously! (Amos 5:23). The prophets' decrying against lack of integrity in the service of God might have had just as well derived from this week's portion of Torah -- Trumah; it presents God's ideas for a worthy Sanctuary, where people may assemble so God may ''dwell in them'', (other than in the Mishkan -- the Tent of Meeting -- that God commanded them to erect to repent and atone for the disgrace of the idolatrous golden calf).

In later generations the Rabbis frowned on Torah students who entered the house of Torah study pretending outwardly to be friendly to their peers but in their heart, they could not stand them. Indeed, the idea that you cannot succeed in Torah learning unless your words and conduct mirrored your true feelings -- or as the talmudic sage Raba has it: ''A Torah scholar whose inside [thoughts] is at variance with his outside [facial or verbal expressions] cannot be deemed as wise'' -- derives from this weekly Parasha -- Trumah.

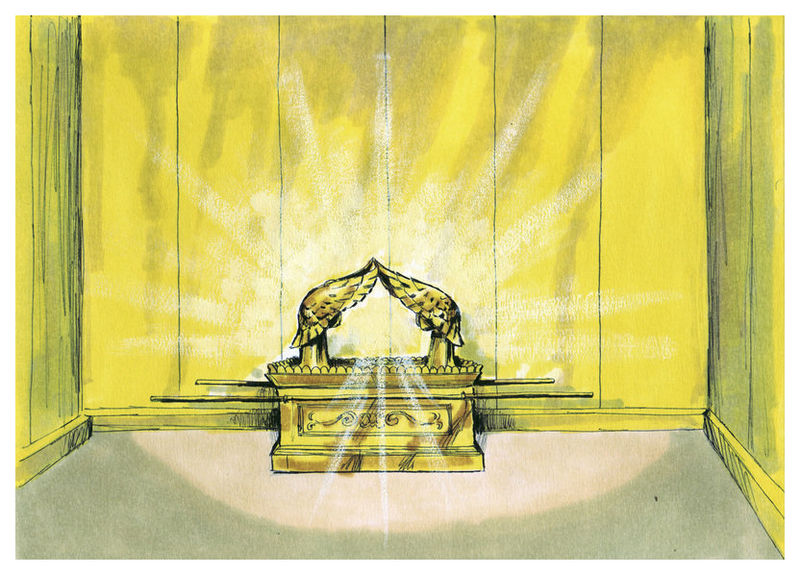

At the beginning of the portion, God commands the Israelites to "make Me a Holy-Shrine that I may dwell amidst within them" (Exodus 25:8). Notably, God did not say "Make Me a Holy-Shrine, so that I may dwell within it." Why, God is in people's good conduct, not in mere goat skin (the material used for the Tabernacle's walls), or subsequently in the glorious stones of the Jerusalem Temple. Now, at the center of the Mishkan (the Holy-Shrine) was the sacred Ark which contained the Tablets of God's Ten Words (The Decalogue). This Ark was a square box, or receptacle, made of acacia wood (rather than use on its construction an edible fruit-yielding tree that was rare in the desert). God, then, directs Moses: "You are to overlay it with pure gold inside and outside'' (v. 11). The need to cover the outside of the Ark with gold is understandable; Why, this is the very symbolic face of Israel's religion, whether in the mobile Sanctuary of Sinai or ultimately in the Jerusalem Temple, and it ought to be visually exceptional in its awe-inspiring effect. But what need is there to overlay the wood on the inside of the Ark as well? Would it not be a flagrant waste of that precious metal that could be spent elsewhere, or kept in reserve for the next generation to decide how to use it productively? After all, who would be looking inside of the sacred Ark -- certainly none but the High Priest, and even then only on Yom Kippurim.

But leaving the inside of the Ark without the gold coating of its facade would be hypocritical, even if the Israelites could only imagine its look. Rabbi Shraga Simmons points out how ''the Hebrew language reveals truths about everyday life. The Hebrew word for face - paneem - is nearly identical to the Hebrew word for interior - p'neem. This teaches that the face we present must reflect our insides. (Contrast this with the English word face, which shares its origins with facade, meaning a deceptive appearance.)'' The Rabbis aversion to one's misleading pretension outwardly by displaying a friendly demeanor to another fellow, whilst harboring ill thoughts of him, has its provenance in God's insistence of coating the invisible insides of the Ark just like its visible outsides.

Hence, our words and facial expressions must express our feelings rather than tell a different story. Similarly, it is incumbent on us to walk our talk; if we advocate a certain idea we ought to make it real in our life through action and behavior. Our verse at hand invites us to be sincere. It is popularly argued that the word ''sincere'' is actually two words: ''sine'' -- Latin for without -- and cera -- meaning wax. Hence, some folklorists explained that dishonest sculptors in Rome or Greece would cover flaws in their work with wax to deceive the viewer (rather than correct such imperfections with the material they worked with originally). Therefore, a sculpture "without wax" (i.e., sin-cere) would mean a work of integrity. To be sincere, rather than hypocritical, is a challenge and a call that derives from the coating by pure gold of the whole Ark, outside and inside it. It is imbued in the divine call to Abraham (and his followers) to ''Walk in My presence! And be wholehearted'' (Genesis 17:1).

[For articles on the “Sabbath of TRUMA" in Hebrew, click here]

![[Picture: When the drought was alarming... Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and Uploaded by _Marion to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/בצורת.jpg)