[For articles on the “Sabbath of Naso " in Hebrew, click here]

Updated on May 23, 2023Rabbi Dr. Yossi Feintuch was born in Afula and holds a Ph.D. in American history from Emory University in Atlanta. He taught American history at Ben-Gurion University.

Author of the book US Policy on Jerusalem (JCCO).

He now serves as rabbi at the Jewish Center in central Oregon. (JCCO).

* * *

This weekly Torah portion, Naso, is the longest among the 54 that comprise the cyclical yearly public readings. The reason for that extraordinary length of 176 verses is the successive repetition in verbatim of five verses at the end of the portion read out tediously even twelve times, like a broken record. But why now, even on this Shabbat, and not at any other time? Homiletically speaking, it is so in order to teach us that we must say what we mean and mean what we say. You see, Naso is the first portion after Shavuot, the day when God gave the people of Israel the Torah at Mt. Sinai, right after they proclaimed: We will do and we will hear/ “na’ase ve-nishma” (Exodus 24:7).

Well, as Shabbat Naso is the first one following Shavuot, Israel is given the opportunity to be true to its collective statement, even as the time needed for hearing the full portion read out is stretched out to the max; no other single public reading has as many as 176 verses. Or in other words, the people Israel proves herein that it does walk its talk! It is willing to dedicate the longest time in the whole year to hear words of Torah as it committed itself to do…

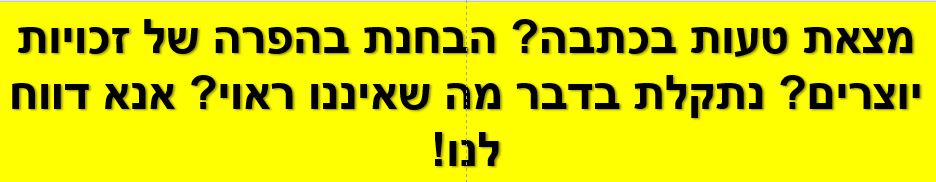

[Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and Uploaded by Pexels to Pixabay]

Nevertheless, what could be the inner meaning of reading out a technical and dry description of the identical gift offering that each of the 12 tribal leaders brought in 12 consecutive days as a part of celebrating the setting up of the Sanctuary? Wouldn’t it be simpler and more practical had the Torah sufficed in noting that each tribal chief brought his personal gift to the Sanctuary on his own designated day, an exactly matching gift of those preceding him that included vessels of silver and gold, fine flour, oil and sacrificial animals? Yet, this isn’t the case. It is apparent that the Torah seeks to make the point that despite the identical gift each tribal leader made, his gift was made independently of the others, not in parroting the others who preceded him, but by investing his own generosity and thoughtfulness. The Torah, therefore, spells out each such present in order not to diminish the individual leader, and to acknowledge his own independent decision, imbued with excitement, in choosing the items of his gift, though they happened to match the other presents that were gifted before his own.

The first one to bring to the Sanctuary his gift was Nachshon, the chieftain – ‘’nasi’’, the elevated one, (or "the prince") – from the tribe of Judah. Yet, only his title is glaringly absent among all other tribal leaders whose title “prince’’ is invoked right before their name.

Quite likely, it is so to highlight the cause of humility. Torah comes to teach us here that being the first of all tribes to present a tribal gift was immensely honorific; there was no need, therefore, ‘’to double down’’ on that honor of being the first presenter, and add the title ‘’prince’’ to boot. Showering excessive honors on a person diminishes the cause of humility.

The same idea is evident, for instance, when the Torah describes Noah honorifically as “a righteous man, [and] blameless in his time. Noah walked with God”; no person in the whole Bible receives such accolades. Yet, when God speaks to Noah for the first time God suffices with one praise only: “For it is you I have seen righteous before Me”. And since humility is an important Torah value, and as Nachshon is the first presenter of a gift to the Sanctuary, this single expression of honor was sufficient for the Torah.

Praising someone excessively might embarrass her and might make her an object of envy among others, if not even inviting hostility. Nachshon enjoyed a good name anyway – the first Israelite according to Jewish lore -- to jump into the raging Red Sea believing that God will part it; one with a bona fide good name needs not words of praise as his name alone evokes respect. On Yitzhak Rabin’s tombstone on Mt. Herzl in Jerusalem only his name is inscribed as a token testimony to his good name and humility.

And finally, the last presenter of gifts was Achira ben Einan, “prince of the children of Naphtali”. Still, Naphtali was not the youngest son of Jacob -- he was his 6th son -- and should not have been the last tribe to present his gift. Rabbi Hanoch extols this tribal leader of Naphtali for volunteering to be the last one among the twelve tribal chieftains simply because of his generous heart. When a squadron of 4 IAF aircrafts bombed the Iraqi nuclear plant in 1981 days before it would become operative, pilot Ilan Ramon (perished later as an Israeli astronaut in the Columbia space shuttle disaster in 2002) volunteered to be the last in the squad. Being the last in the squad exposes that aircraft to the most danger of being shot down on the way back to home base. Ilan Ramon decided to volunteer to be the last one though he outranked some of his other fellow pilots; if one of the 4 pilots had to be shot down it would better be him as he alone among his fellow squad members did not have children yet ... Volunteering to be last testifies to having a generous heart, indeed, not unlike the chieftain of the tribe of Benjamin.

[For articles on the “Sabbath of Naso " in Hebrew, click here]

![[In the picture: This weekly Torah portion, Naso, is the longest among the 54 that comprise the cyclical yearly public readings. The reason for that extraordinary length of 176 verses is the successive repetition in the verbatim of five verses at the end of the portion readout tediously even twelve times, like a broken record... Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and Uploaded by Pexels to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/תהילים.jpg)

![[Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and Uploaded by Pexels to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/פסוקים.jpg)

![[The original image is a free image - CC0 Creative Commons - designed and uploaded by blickpixel to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/מתנות.jpg)

![[The original image is a free image - CC0 Creative Commons - designed and uploaded by Bellahu123 to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/מתנה.jpg)