[For articles on the “Sabbath of Mishpatim" in Hebrew, click here]

Updated on February 12, 2023Rabbi Dr. Yossi Feintuch was born in Afula and holds a Ph.D. in American history from Emory University in Atlanta. He taught American history at Ben-Gurion University.

Author of the book US Policy on Jerusalem.

He is the rabbi of Congregation Shalom Bayit in Bend, Oregon.

* * *

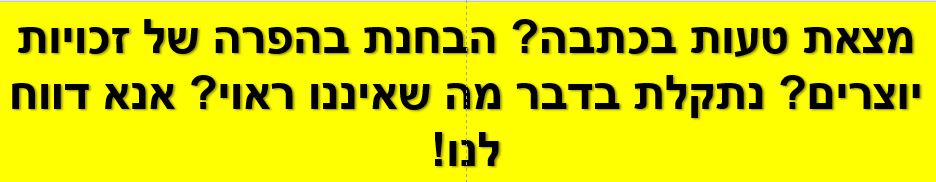

Twice a day after reciting the Sh'ma we continue on to the divine commandment that forbids us to ''go off after the lusts of your heart or after what catches your eye, so that you remember to do all my mitzvot and be holy for your God'' (Numbers 15:39). The message here is clear to see; our daily temptations to follow astray either our heart or eye are tangible and real. Despite our attempts to fulfill God's Word, the distractions on our path loom large.

It is against this background that we note God's command to Moses in this weekly Torah portion: ''Go up to Me to the mountain and remain there, that I may give you the tablets of stone'' (Exodus 24:12). Now, since God is not verbose, what is the purpose of the two ‘’gratuitous’’ words ''remain there'' when Moses is already ''on the mountain''? What else can he do but stay on Mt. Sinai's peak until God has given him the Tablets of the Covenant? It seems as though ''go up to Me to the mountain'' should have sufficed and the extra divine call to Moses ''and be [or remain] there'' was a mere excessive wordiness.

Truth of the matter is that none of the traditional commentators deliberated on that ostensible redundancy. The Kotsker Rebbe, however, noticed it and he was quoted thusly about it: ''It is an attestation that even he who exerts himself and scales the summit, could, indeed, reach it, but might not still be there after all. Indeed, he stands on the mountain, but his head could wander off and be in a different place. The essential thing is not the climbing up but the being there, earnestly so, and only there, rather than being simultaneously in both places, on the top of and on the bottom of the mountain.

According to this acute insight even a man like Moses could wander off with his thoughts and sail away with them when he needed to be totally attentive to God's instructions and elaborations. Had Moses allowed himself to be distracted by other thoughts he could have ended up hearing God's voice saying ''beh-khelev'', rather than ''bah-khalev'', which would have made the difference between God prohibiting the cooking/selling/eating of a kid in its mother's fat (khelev), rather than in its mother milk (kalev)…

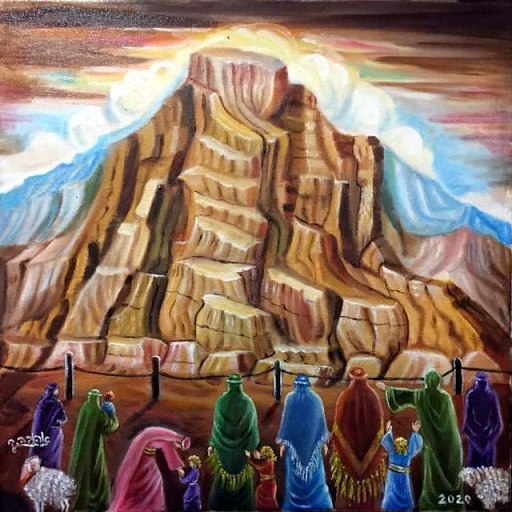

Many years later Solomon, the illustrious king of Israel, who had built the Jerusalem Temple did not remember that lesson despite his celebrated wisdom, and his iconic words on the day that the Temple was inaugurated, urging his people to ''incline our hearts unto Him, to walk in all His ways, and to keep His commandments, and His statutes, and His judgments, which He commanded our fathers'' (1K 8:58). Nevertheless in his later years Solomon did not stay focused on that goal and heeded instead the call of his heart and eye by marrying 700 foreign wives and adding to them 300 mistresses who ''inclined his heart to follow other gods, so his heart with God was no longer whole'' (11:4). He, who wrote at a younger age the warning: ''My son, stay focused unto my wisdom... for the lips of a foreign woman drop honey... [whilst] her ways wander... Remove thy way far from her''... (Proverbs 5: 1,3,6,8) allowed himself to take his sight of the ball.

No wonder God called upon Moses to stay focused on the mega task ahead -- bringing both the written and oral Torahs to the people. And without focus and determination one drifts off and can't achieve anything; something that could be too dangerous if done while driving a vehicle on the road, in the hospital OR, or in not fastening completely that bolt in a critical place of the aircraft.

Multitasking -- doing simultaneously two different things, writes Gilad Peled, is a recipe to a colossal failure; doing either task would be a wasted effort. Multitasking brings us to do less, experience more stress, and perform less productively and efficiently in comparison to the one who dedicates himself to one assignment without allowing for distractions. In telling Moses to ''be there'' after he already had climbed Mt. Sinai, God wanted Moses to dedicate himself fully to the task of transmitting His Word to the people without erring. In short, God did not want Moses to multitask because the human brain is not built to pay adequate attention to more than one demanding task at the same time. And this may very well be the answer to God's ostensible ''wordiness'' in that verse at hand.

[For articles on the “Sabbath of Mishpatim" in Hebrew, click here]

![[Picture: our daily temptations to follow astray either our heart or eye are tangible and real... Free Image - CC0 Creative Commons - Designed and Uploaded by DenisDoukhan to Pixabay]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/פיתויים.jpg)

![[Picture: Many years later Solomon, the illustrious king of Israel, who had built the Jerusalem Temple did not remember that lesson despite his celebrated wisdom... The Temple model. The image was created and uploaded to Wikipedia by Christoph Braun. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license]](https://www.xn--7dbl2a.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/בית-המקדש-הראשון.jpg)